Tactics small businesses can learn from product startups to drive growth

The following is from a presentation at our Digital Marketing Breakfast series in September 2019 by Andy Farrell. It’s been edited for clarity.

What is a Startup?

A startup is very much a human institution. It’s about people working together to try to solve a problem that hopefully, other people care about, and they do that typically with some kind of vision around the particular product or service that they’re looking to deliver.

But of course, at the start of that process, startups normally have no idea whether they’re actually shooting at a real problem and that creates a high level of uncertainty. Really that’s what we, I believe, can learn a lot from. They won’t know how the product or service they’re working on is going to look, how it’s going to work or how it will be built. And it’s that uncertainty factor that makes startup thinking very interesting.

There are roughly a hundred million startups that appear every year, that’s about three startups per second. In Australian dollars, approximately $300 billion is invested globally and in Australia, even Jobs New South Wales has gotten in on the act, if you got a hot idea and you can convince them to give you some money, they’ll actually match the first $25,000 in funding to get something off the ground. So it’s an interesting space to be in.

Startups come in different shapes and sizes. But generally, you can say they start off typically short on cash, short on time and they’re high in risk. In Australia and globally we’re starting to see those factors are becoming a driving concern for many businesses, not just startups. So with so much at stake and a couple of decades now and with a horde of experience and so much analysis that’s gone around why startups fail and why they succeed, the whole business of startups has become something of a science.

The 5 Factors of Startup Success

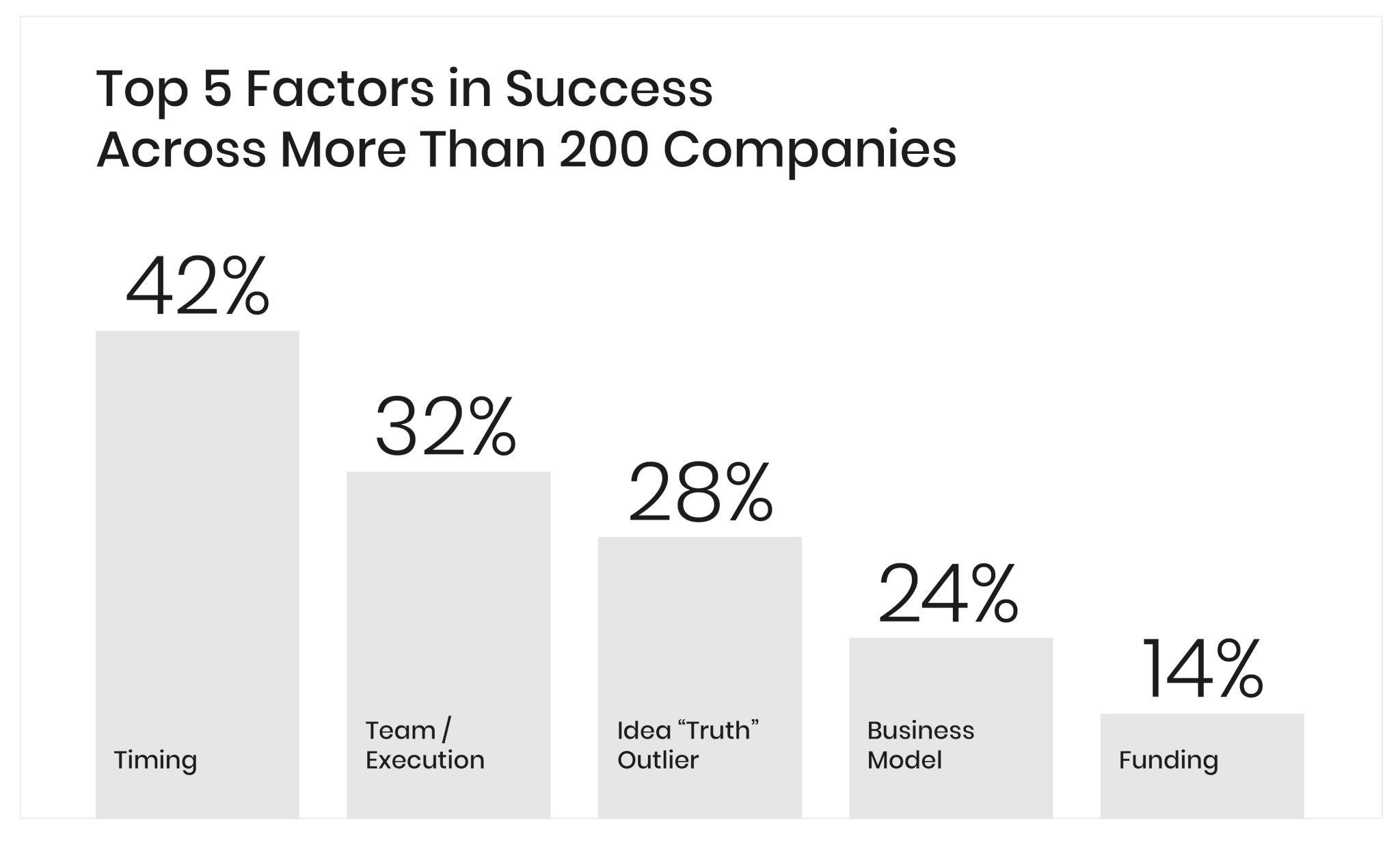

One of the myths that’s pretty thoroughly dispelled now is this idea that it’s really all about just having some amazing big idea and if you can just figure out what that is, then you’re home and hosed. As it turns out, that’s not the case, ideas obviously do still count but they’re not actually the most important thing in terms of success.

So what does matter? Bill T Gross founded a tech company called Idealab. They’ve helped to build 150 companies and created some 10,000 jobs and have also had 45 successful IPOs and acquisitions. They had a look at close to 200 companies that they’re serving, trying to figure out how they succeeded, what was it that really mattered most. And the number one thing as it turns out is timing.

- Timing

- Team / Execution

- Idea “Truth” Outlier

- Business Model

- Funding

Can you think back to the name of the video streaming platform out about two years before YouTube? No. That’s because of timing.

What were the big two social media networks that happened before Facebook? MySpace and Friendster, gone. Why are they gone? Timing.

So timing is an important factor, and obviously there’s a whole bunch of other factors besides timing. In the image above, you’ll see that at number three, ideas still do matter. The important thing to clarify here is that Bill’s talking about having a truly novel or differentiating idea. We drill into this a little bit more, another way at looking at success factors is the actual way startups approach problems. A lot of this is quite well understood now in terms of how can you actually validate the idea of growing a business from zero to one successfully with the least amount of pain.

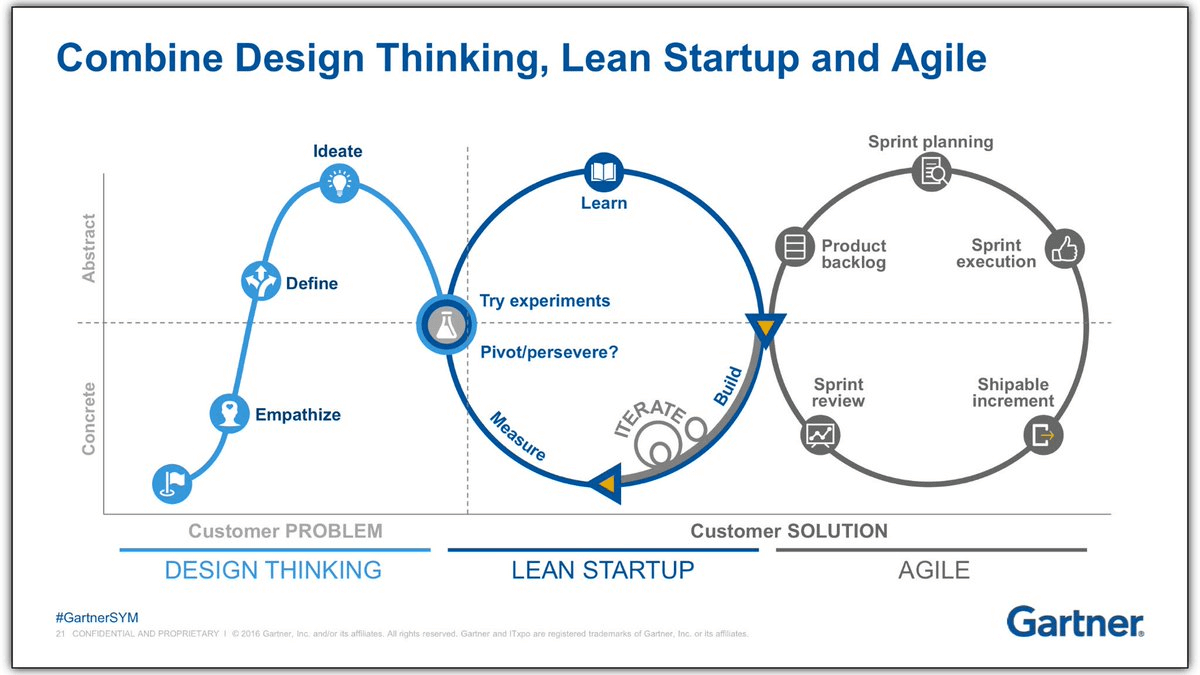

Some of these things you may have heard of and today we’re not going to try and go into all the detail around what’s involved here. But we are going to pick out some specific tactics we see working and could be applied practically. Some of this stuff you may have heard of, so things like Design Thinking, Lean Startup, Agile are frameworks that we see used across businesses quite widely nowadays.

How to Eliminate Risk in Startups

One of the core principles is trying to eliminate risk and look at ways of validating new ideas, new products, new services without having to bet the house. The sad thing you often see is people get so excited about their idea, whether it’s an existing business for which they have a new product or service or whether it’s a startup or something that they think is going to change the world, they rush to get it to market, because they’re convinced it’s going to work and when the curtain is drawn, crickets… Nobody cares.

That’s the reality, most startups fail and a lot of small businesses fail. A lot of product launches don’t work out so this is really all about seeing if we can figure out if there’s a process that we can go through that can help us achieve that moment of failure sooner or figure out how can we alter our ideas and validate them sooner so we get them right.

Let’s look at practical examples of how a large organization has adopted this kind of startup thinking and actually uncovered something that’s quite illuminating. Imagine you’re a toothbrush manufacturer and you realize that kids toothbrushes have become commoditised, they’re not selling like they used to, so you want something new and exciting to try to cut through the noise and actually back get back some of your old sales. So you approach an organization that’s going to help you with defining what that new product is, and you tell them what it is that you want to achieve.

Oral B had this problem and they went to a guy named Tom Kelley. When you think about a kids toothbrush, and somebody says, what do you need to get right about a kids toothbrush, you probably think, what’s the difference between adults’ hands and kids’ hands. They’re smaller, so what’s the obvious thing to do? What would you do with a kid’s toothbrush that’s different? Make it smaller.

And that’s what they were doing. Everyone in the market at that time was producing little kids’ toothbrushes. So this company Tom Kelley headed up thought, we should go out and actually do a real study and observe kids brushing their teeth and figure out, is that actually the problem that we’re solving? And originally Oral B was, no, this is an obvious thing before agreeing to proceed.

So day one, they’re sitting, watching kids brush their teeth and they notice kids hold their brush differently to adults because their hands are smaller, but they don’t have the dexterity balance. So actually they have a whole different problem and they realized the solution was actually not to make small toothbrushes but it was to make fat toothbrushes.

Oral-B changed and rolled out their new fat toothbrushes and for 18 months they had the biggest selling toothbrushes in the world. Of course, nowadays that’s pretty much the standard when you go and buy a kid’s toothbrush.

The lesson there, which is fundamentally what startups try to do, is to never assume that you truly understand the customer problem. But to actually take the time to step back, get into the same headspace that customers are in and observe what they’re actually doing.

One of the characters that I like to bring up as kind of a guideline to this kind of thinking is someone that you might recognize as he was very popular on the TV shows back in the ‘80s. That is a character called Columbo and he was an investigator.

Columbo had this very unusual style. He was very good at just talking to people. And he would start a conversation and just ask questions and gradually get them to divulge information without actually drilling them about things or specifically asking incriminating questions, he would just have a chat.

How to do Customer Interviews

That approach is actually the exact strategy that startups are following. Startups are figuring out ways to start a conversation with customers that can reveal insights, that’s completely backwards to how we usually think about getting customers opinions about things. Quite often you run a survey and ask people what they think they want, or do a focus group, or get everybody to talk about how they see the future. As it turns out, people are pretty bad at knowing confidently what they actually will do in the future

Another great example to mention is a case study in either the book Freakonomics or Tipping Point (I think?). That’s where Sony had a large focus group and during the focus group, they said they were rolling out two colours, the hot pink one and a black one, which would you buy? Everyone was feeling very hip and said definitely the pink one. It was by far the most popular choice with 90+ percent of the audience ticking the pink box. At the end of the day, the speaker said, as a thank you for participating we’ve actually got one of these that you can take home with you and enjoy. On their way out they could pick up a black one on the right-hand side and a pink one on the left-hand. You know what’s coming, don’t you! The black ones disappeared and the pink ones stayed, completely the opposite of what everybody said.

This is one of the challenges. What you would normally consider to be a reliable way of understanding customers can turn out to be extremely misleading. The only thing that we can 100% confidently rely on, is observed behaviour. And if you can’t observe behaviour you can at least try and drill in on past behaviour, so at least that’s certainly way more reliable than relying on the claims made about future choices.

It’s quite an art engaging in these kinds of conversations when doing customer interviews and not leading a person toward a particular assumption or outcome that you’re hoping to uncover. So you might ask questions such as:

- Think back to the last time you blah, blah, blah

- Tell me a story about something that happened in the past

- Tell me about the time when, and so on

- How would you feel when, and then ask them about something that maybe you’re trying to solicit an emotional sense of what they were feeling when they did something

- Why do you do such and such?

You’ll notice all of those questions are retrospective, about how we remember the past, we’re drilling into actual behaviour, things that someone is already doing.

This is a strategy that you can apply to anything where you are trying to figure out what’s the right way to improve something. Whether it’s product or service, whether it’s some process that you use where you’ve got customers but you’re just trying to figure out what’s their actual perspective of my business. How can we figure out ways to improve, what are the real problems they’re actually having.

The kind of conversations we don’t want to have are the ones that typically people are having, which is where you say:

- Imagine if we did this, what would you think about that?

- Do you think maybe we should do, blah?

- What features do you think that we should add?

Have you heard those questions before? People always have a long list of features that we think they should have. Then when it comes to whether or not they actually use the features, that’s usually a different story. So don’t ask leading questions, don’t offer judgment. Be Columbo.

How to Understand User Behaviour

Now in the digital space, there are some interesting tools around where we can study behaviour. The common tool people mention to us when referring to how people are using their platform is Google Analytics. We start hearing Google Analytics numbers being quoted, oh we get this many page views, we get this many clicks.

There are other tools such as Hot Jar, which has a free membership tier. And what it’s doing is tracking where people move their mouse and where they click. The interesting thing with that is there’s a strong correlation between where the mouse is on the screen and where people are actually looking. This can tell you a lot about somebody’s attention, what’s actually getting their attention and what they’re doing. The next thing, when we track the mouse movements and mouse clicks, we can see these little hotspots of where someone has clicked and some of those clicks don’t go anywhere. So unlike Google Analytics which is telling you what happened, this can tell you what the person is trying to make happen, it’s a whole different story, isn’t it?

![]()

So this is totally about behaviour, you can even playback a video that shows you individual users and how their mouse moves around a page and you can get clues, you follow what they are doing, where they are clicking or not clicking you can get all these little clues around problems that we can fix.

Understanding user behaviour can include collecting data, it can include having conversations, there are lots and lots of other tools out there that are quite useful that are able to drill into this space. This is a strategy we’re using a lot with customers now, not just when we’re starting something brand new either, but quite often we’re just trying to figure out what’s working and what’s not working on just a regular website, this approach could be useful.

Learn, Build Measure

Sometimes businesses sit back and look at all the challenges out there and attempt to gather this information and feel there’s so much chaos, so much information to gather, maybe we should just do it, you know, let’s just get something out there and see what happens. And that might sound really bold and brave, but unfortunately, it’s usually a recipe for disaster. The solution to just doing it, is a model called Learn, Build, Measure. This was defined by a guy called Eric Ries author of a fantastic book, if you haven’t read it it’s worth picking up, called The Lean Startup. The idea behind The Lean Startup is since startups are operating usually on a shoestring and often there’s a finite timeframe within which they need to achieve an outcome, cost & time are both an imperative. So being lean or trying to keep costs down and get outcomes very quickly is essential. It’s basically one of the underlying philosophies behind this approach and that’s something that businesses generally can benefit from.

The approach is to go around a cycle, building things, measuring what happens and learning. When you actually implement something and start the work, the first thing you want to do is figure out what is it that we want to learn? And the thinking is much like science 101, you’re coming up with a hypothesis: we think if this happens, that will happen. For example, you might say:

- We think that commuters want to order stuff on the way to work, an app for food;

- Or maybe you’re a furniture company and you might think that people will be happy to assemble their own furniture, if it’s good quality and it’s a lower price, that’s turned out to be true.

The skill really is being able to test a hypothesis effectively without having to bet the house.

Test your Hypothesis with an MVP (Minimum Viable Product)

One way to test a hypothesis is to build an MVP (Minimum Viable Product). It doesn’t mean you’re building something that’s kind of broken and then you’re gradually adding to it till it works. What it means is, you figure out what is the most basic piece of value that you are hoping to deliver, what is the basic problem that you’re looking to solve and what’s the most simple expression of that you can come up with to actually test and evaluate like that. So that’s where you build that first version of that minimum viable product and then go out there and study what happens when people are exposed to it. And as time goes along, learn what it is that’s actually resonating with people and you start to gradually improve and iterate till you get to the end result that’s actually going to be your business.

Smoke Test your Hypothesis

Sometimes you don’t need to actually build anything. This approach is something we’ve been trialling a lot more these days and it’s what we call a smoke test. The term smoke test comes from electronics and it’s the most simple test that you can do to test a circuit. Imagine you’ve built something really big and complicated, with lots of moving parts, something electronic and what’s the simplest test you can do to figure out whether it’s going to work, well it’s to switch it on very quickly and check for smoke. No smoke, you’re off to a good start. That’s the basic concept, it’s working out what is the most rudimentary way of checking if something is going to work or not.

In digital, the typical way we do this is to create a landing page and it might be talking about a product that we’re hoping to build, it doesn’t mean we’ve built the product, it doesn’t mean we’ve created the service. It’s just testing an idea. So how it typically works is you go out to Facebook or Google and you buy some attention. You drive people to this landing page, and you’ve probably seen this, where you go somewhere, thinking, great, this sounds cool, I’ll sign up. And then when you sign up it says, we’ll let you know when it’s launching, it’s a few months away or maybe you’re in a queue or something interesting like that.

Smoke tests are a valid way of testing anything that you’re wanting to try out. Rather than rushing to market, just conduct a little test to see whether you actually get the engagement on Facebook, and check:

- Do people even click on your ads?

- Are the keywords resonating with people?

When they get to your page use Google Analytics and use Hot Jar to track:

- Where does their mouse go?

- Where did they look on the page?

- What propositions are you making on this page that is actually getting engagement?

- Where are they pausing the mouse?

Typically you can put something up which has half a dozen features, you’re not really sure which ones you’re going to build. And just depending on where the attention goes, you might even re-prioritize your entire strategy just based on the actual behaviour you observe.

Going back into a real-world case example, pretend you’re running a restaurant and you’re thinking ah, I want to try a new line and we’re going to do smoked slow-cooked meat. That’s actually quite a big deal to set it all up, ordering equipment, reconfiguring a kitchen, what if nobody wants it in the end? Maybe we’re just the wrong kind of restaurant? So a simple example for a restaurant would be to put that on the menu, maybe you only distribute a few of those menus that have the new dishes and when your waiters take orders for it, you can just tell them, oh sorry we’re actually just sold out. So you didn’t actually have to cook anything, you didn’t have to order any product or equipment and you’ve run a test to see, did people have interest in ordering this before you go to all the trouble of re-tooling your kitchen and ordering and preparing.

So you get the idea, try to figure out experiments that you can run to validate ideas and remove the risk.

Wrapping Up

So to recap.

- Learning: What do we want to know? Figure out your hypothesis upfront.

- Building: Coming up with the most simple test that you can possibly imagine or the most simple expression of the new product or service something rudimentary that you can observe customers.

- Measuring: How do customers respond? Figuring out new ways to measure, as you saw with Hot Jar, the tools are out there.

- Learn: Continue to iterate.

So you notice that’s a cycle. That’s one of the things Startups are really good at is iterating their processes. Not feeling like they need to deliver the finished thing on day one, but realizing that iteration is the path to success.

Sometimes it means you’ll fail, the trick is to fail early. But often it provides an opportunity to uncover a change in direction that’s going to work and maybe you’ve got a success on your hands and you can start scaling it up.

This approach we’ve been applying at a lot of our customers, we’ve actually been doing some product development internally nowadays and we’re also working with clients who are involved in building a lot of products and we’re applying these strategies to great successes.

The other thing we’re doing is around applying this thinking to our digital marketing strategies and process around how we test new campaigns, how we evolve our thinking around what particular segments to focus on and so on, so there’s a lot of different ways for this kind of thinking to work.